Featured Viewpoint by Blake Hall | January 20, 2022

Executive Summary

ID.me stands by its estimate of $400 billion in fraudulent claims for unemployment insurance during the pandemic. Here’s a summary of the evidence:

- Over $1 trillion was spent on unemployment benefits, according to the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC).1

- State workforce agencies were not equipped to perform identity verification, which created huge opportunities for fraud. Criminals shared fraud methods on the dark web.

- States have reported massive fraud losses in the billions of dollars, including Arizona, California, Michigan and Nebraska, but many states do not have systems in place to detect and report fraud. In those states, fraud losses are likely even higher.

- For the period March 27, 2020 to September 30, 2020, DOL’s Inspector General found that 60% of states did not complete required reporting for fraudulent payments.2

- Multiple experts have corroborated estimates of hundreds of billions of dollars of fraud losses nationwide.

- ID.me’s view of identity and eligibility fraud in the 27 states we support is likely the first integrated assessment of fraud trends.

- ID.me has substantial additional evidence of identity theft fraud that state audits do not have the ability to detect.

- ID.me will be releasing a comprehensive Unemployment After Action Report in the coming weeks.

- It will likely take years for states to fully audit the fraud during the pandemic. Meanwhile, all available data from the states, experts, and ID.me supports $400 billion dollars lost.

Unemployment benefits are administered at the state level

States differ in their technological maturity, their ability to detect improper payments, and with respect to compliance with Department of Labor (DOL) requirements. This reality makes it difficult for the federal government to rapidly and reliably quantify fraud at a national level as antiquated technology prevents accurate reporting just as those systems proved unable to stop fraud while efficiently delivering benefits.

Historically, eligibility requirements in the states protected the program from bad actors who would seek to steal government benefits. Employers were notified, and could contest, UI payments for employees who lost their job involuntarily and not for cause. As a result, employers provided an effective check against fraud. Success rates were relatively low, the process is fairly involved, and the weekly payouts were lower than during the pandemic. In Virginia, UI payouts range from a $60 weekly minimum to a $378 weekly maximum.3

The Payment Integrity Information Act (PIIA) requires programs to report an annual improper payment rate below 10 percent. Improper payments can include overpayments to eligible individuals e.g., a person finding a job but still receiving UI payments for several weeks. Unprecedented and sudden reform to the UI system during the pandemic shattered the existing protections in place to combat fraud while sweetening the pot for fraudsters.

Given this background, there is a concerning lack of transparency tied to improper payments that persists today. Many states cannot detect fraud at all, let alone report it. In a May 28, 2021 report, DOL’s Inspector General listed the following in a section titled “STATES DID NOT REPORT OVERPAYMENTS AND FRAUDULENT PAYMENTS:” 4

- For the period March 2020-September 2020, 42% of states did not complete required reporting for overpayments and 60% did not complete reporting for fraudulent payments.

- 60% of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) states, 38% of the Federal Unemployment Compensation Program (FPUC), and 45% of the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) reported No Fraudulent Payments.

- Officials in 17/50 states (34%) reported their IT systems did not allow them to complete improper payment detection and recovery.

The Inspector General’s report asserts that states were either not reporting, or underreporting, fraud and improper payments. This situation is attributable to decades of chronic underfunding and to a slew of new programs that overwhelmed state agencies.

What the states are saying

Despite these reporting deficiencies, states have already published massive fraud losses:

- Michigan reported losing $8.5 billion dollars in fraud according to a recent audit by Deloitte.5 Michigan has a population of slightly less than 10 million people. Calculated on a national basis, the percentage of identified fraud would equate to $281 billion dollars.

- Arizona reported $5.8 billion dollars in fraud6 (though they were able to recover $1.4 billion). Arizona has a population of about 7.3 million people. Calculated on a national basis, this would equate to $262 billion dollars in fraud.

- California reported $20 billion dollars in fraud.7 Calculating the per capita rate on a national basis, the total lost would equate to $167 billion dollars in fraud.

- A 2020 audit of improper unemployment payments in Nebraska found that two-thirds of money was misspent.8

These figures are based primarily on identity theft, cross-matching, and associated overpayments tied to the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program in particular. Eligibility fraud (i.e., people applying for unemployment in states where they are not eligible, prisoners, people who are employed, etc.) that went undetected and fraud targeted at programs other than PUA that weren’t audited will increase these numbers further. Overpayments to eligible claimants will increase the total amount lost beyond explicit fraud as well.

Notably, California and Arizona were the first states to implement identity verification and other fraud tools that conformed to the NIST 800-63-3 Identity Assurance Level 2 and Authenticator Assurance Level 2 standards. It is rational to believe the fraud rate was worse in slower moving states and in states that lack the ability to detect or report fraud at all.

What the experts are saying

Multiple cybersecurity experts, analysts, and law enforcement officials corroborate hundreds of billions of dollars of loss in line with ID.me’s estimates of $400 billion, about a 40% loss rate:

Rachel Greszler, Research Fellow in Economics, Budgets, and Entitlements at the Heritage Foundation, testified before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection (August 2021): “My analysis estimates that $357 billion worth of payments will have gone to non-unemployed individuals…While some states have successfully recovered hundreds of millions, or up to a couple billion dollars, total recoveries will likely pale in comparison to the magnitude of fraud.”9

Jon Coss, who heads a unit within Thomson Reuters that is helping states detect fake unemployment insurance claims, is on record saying that, “From my experience, when this is all said and done, we are going to be counting in the hundreds of billions of dollars, not the tens of billions.” The U.S. Department of Labor’s inspector general estimated that at least $87 billion in fraudulent and improper payments were going to be processed by September 2021, which was based on a historic assumption of 10% fraud—but he acknowledged that figure is likely too conservative where fraud has “exploded” to “unprecedented” levels. Instead, Coss noted that “between 40% and 50% of the claims his group has analyzed seem highly suspect.”10

On July 1 2021, “Supervisory Special Agent Keith Givens, with the FBI in Orlando, told [investigators] they have reports of up to $250 billion in unemployment fraud nationwide.” Enhanced unemployment benefits did not end until September 6, 2021.11

“David Prosnitz, president of Personnel Planners, said bogus claims typically make up less than 1% of the claims his firm sees when assisting employers with unemployment insurance issues. But during certain periods of the pandemic, that share has surged to upwards of 50% of claims, he said.” This fraud was explicitly tied to Traditional UI claims and not to the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program that crime rings targeted initially.12

Douglas Holmes, president of UWC – Strategic Services on Unemployment & Workers’ Compensation, an advocacy organization for businesses, told Bloomberg Law: “Fraud rings look for easy targets that produce revenue with minimal risk…When PUA is no longer on the board, they’ll look to other places to exploit. They’ll look to regular UI.”

Crane Hasshold, senior director of threat research at Agari, a cybersecurity research firm, told NBC News “They (Nigerian crime rings) are seeing essentially trillions of dollars that is up for grabs. This is their World Series. This is their Super Bowl.” 13

What DOL’s Office of the Inspector General is saying

The Department of Labor’s Inspector General site notes that improper payments tied to unemployment insurance total at least $87 billion.14 However, this estimation uses the improper payment rate from prior to the pandemic and before the “Super Bowl” of fraud kicked off. DOL’s Inspector General noted that based on initial findings “the (pandemic) rate will be higher than 10%.” Given the increased fraud rates, this approach underestimates the actual levels of fraud.

Additionally, many states removed or relaxed the eligibility requirements they had in place for the traditional UI system. 35 states waived the one-week waiting period before distribution of traditional UI benefits. 16 states decided UI claims would not be charged against an employer’s experience rating – a metric that can lead to higher UI charges for an employer – to discourage employers from contesting claims.15 California and Florida suspended UI certification and Michigan relaxed checks due to the massive number of claims filed.16 17 18

Given these actions, employers that typically serve as the identity verification and eligibility adjudication gatekeepers with state workforce agencies were either removed from the claims certification process or had reduced incentives to report fraudulent claims. To Florida and California’s credit, they were among the very first states to adopt identity verification. However, identity verification and eligibility verification are two different controls, opening the door to out-of -state applicants who could use their own identity to fraudulently apply for aid in those states.

What the data says about eligibility fraud

Eligibility fraud exploded during the pandemic. Eligibility fraud is distinct from identity fraud in that the person who is verifying their identity is that person – they just aren’t eligible in the state where they are applying. While states should use a national clearinghouse to check if an identity filed a claim in another state, many of them do not cross-check claims. A May 21, 2021 Department of Labor Inspector General report found that 44 of 50 states (88%) did not perform all eight recommended cross-matches for claims.19 By contrast, ID.me as a shared service for login and identity verification is inherently networked across all states.

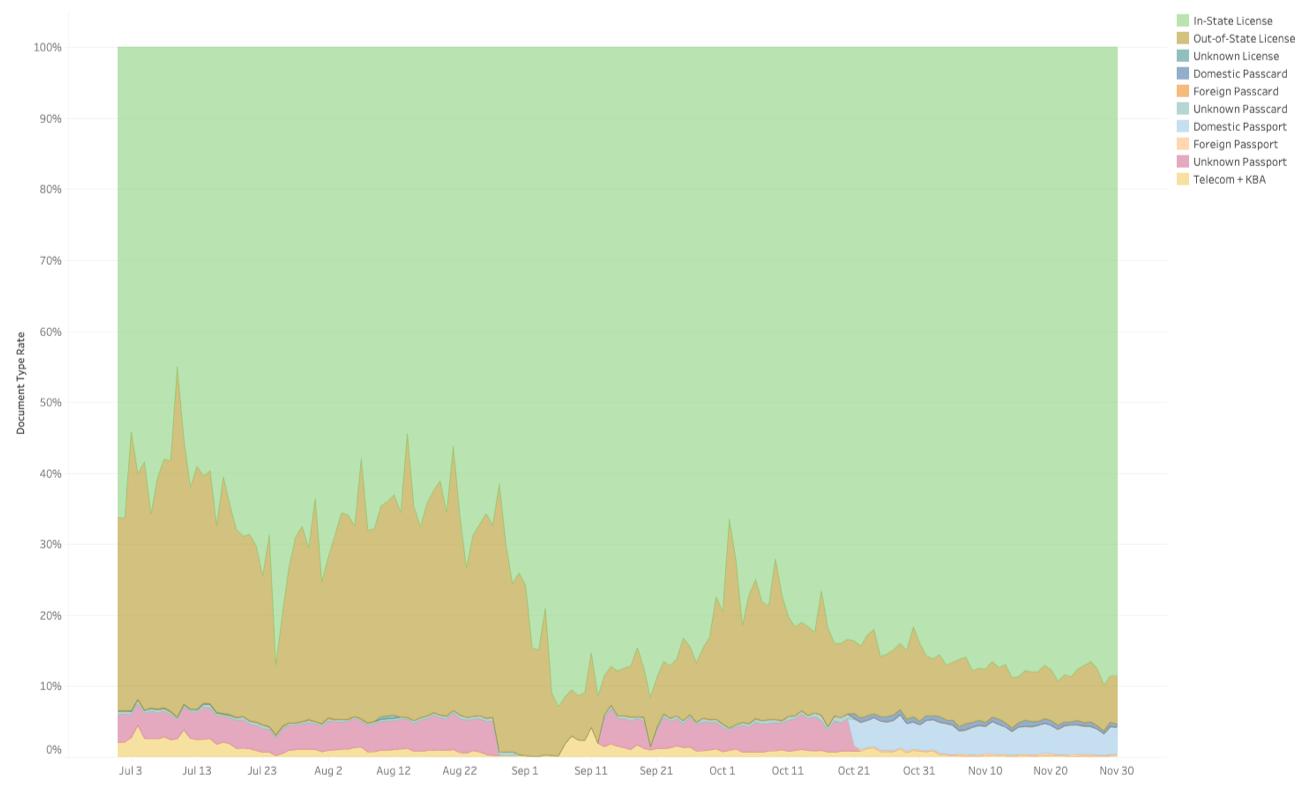

Due to our network, ID.me can monitor two key metrics that provide insight into eligibility fraud. First, we can see if the same person/identity is applying for unemployment in multiple states. Second, we can see the percentage of the time that a person’s state issued government ID matches, or does not match, the state where that person is applying for unemployment benefits.On July 10, 2021, out of state licenses as a percentage of identities verified for a given state peaked at 66.2%. On September 6, 2021, the day that enhanced federal unemployment benefits ended, the percentage of out-of-state government IDs used for identity verification dropped from 30.2% to 10.7%. The rate briefly rose again when individuals realized they could still apply for unemployment benefits retroactively. ID.me monitored the dark web chat rooms where people shared this information about eligibility fraud with each other. During this period in October, out of state licenses rose to 49.1% of identities used to verify in a given state.

Once the retroactive application date expired, out-of-state government IDs fell back to 7 – 11%, which appears to be the steady state range absent substantial fraudulent attacks.

Figure 1 below shows the massive drop in out of state applicants when enhanced federal benefits ended. Eligibility fraud on an industrial scale is the only plausible explanation.

Considering that 17 of 50 states (34%) told DOL’s Inspector General their IT systems do not allow them to complete improper payment detection and recovery, ID.me’s view of identity and eligibility fraud in the 27 states we support is likely the first integrated assessment of fraud trends.20 This status quo means that fraud is underreported. If 17 of 50 states cannot detect it at all, then it is unlikely the remaining states can capture all of it accurately.

ID.me’s video chat verification team monitored significant patterns that support massive eligibility fraud. One video chat agent wrote to ID.me’s executive leadership team that she was having trouble sleeping after verifying tens of people with state licenses from the South who were applying for unemployment benefits in Western states. These out of state applicants should be audited retroactively as the percentage of ineligible claims is likely very high.

The quantitative data and the qualitative feedback from help desk agents points strongly towards record eligibility fraud. This eligibility fraud will stack on top of identity theft fraud.

ID.me has substantial additional evidence of fraud patterns that state auditors likely do not have the ability to detect. We will be releasing a comprehensive Unemployment After Action Report detailing all of these topics and how fraud attacks changed over time in the coming weeks.

What the data says about identity fraud

The introduction of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program introduced an entirely new attack vector. For this program, anyone could verify their identity and self-assert eligibility i.e. self-employed, sharing economy worker, etc. By all accounts, the fraud targeting this program was astronomical and likely dwarfs eligibility fraud. International crime rings, foreign students, Nuke Bizzle, a Memphis rapper, and more began targeting unemployment.

ID.me’s analysis of PUA claims signals fraud occurred in over 50% of all claims filed in multiple states. An early review in Nebraska, which looked at all statewide payments through June 2020, found roughly 66 percent of unemployment money was misspent.21

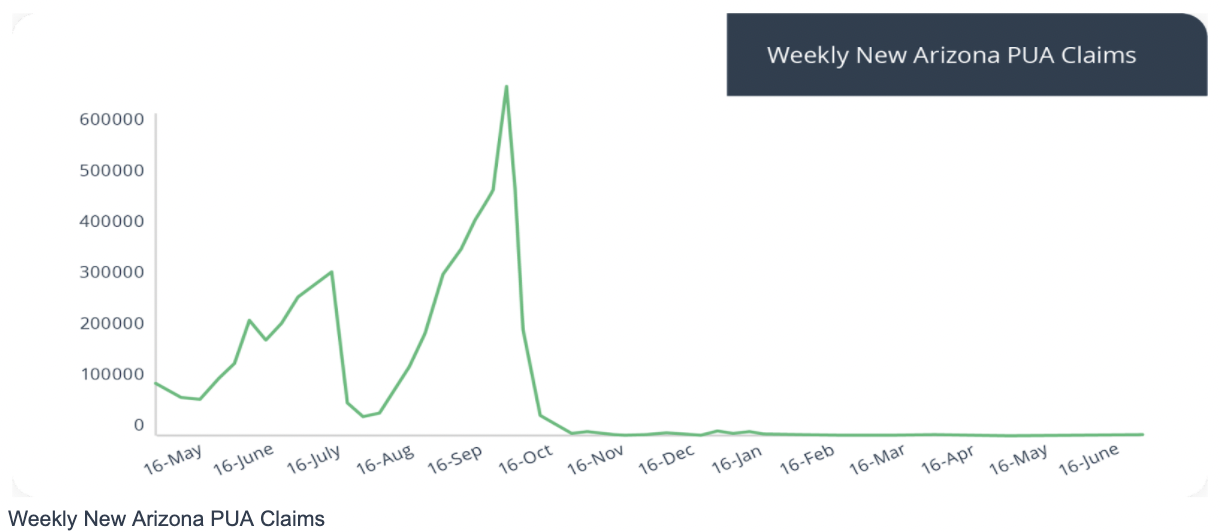

The dropoff in claims filed after implementation of ID.me provides evidence of the enormous magnitude of fraudulent claims as criminals would rather abandon a state than risk leaving a trail of their fraud in ID.me’s verification process. Arizona provided a testimonial of this impact, “Due to the significant decrease in new suspected fraudulent claims from a record high of nearly 570,400 claims filed the week ending October 10th, compared to just 6,700 the week ending November 12th after the implementation of ID.me, DES is expanding this partnership to detect fraud among existing claimants.”22

After Arizona applied ID.me verification to continued PUA claims, on December 4, 2020, continued claims decreased by 68.3%, virtually all of which were confirmed as fraudulent. Out of 268,556 existing claims, only 85,174 of those claims were legitimate.

Publicly available data demonstrates an immense scale of fraud perpetrated across the country, in Colorado, New York, Florida, California, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, and the list goes on. We can help anyone interested in diving into these numbers to access publicly available data that corroborates it.

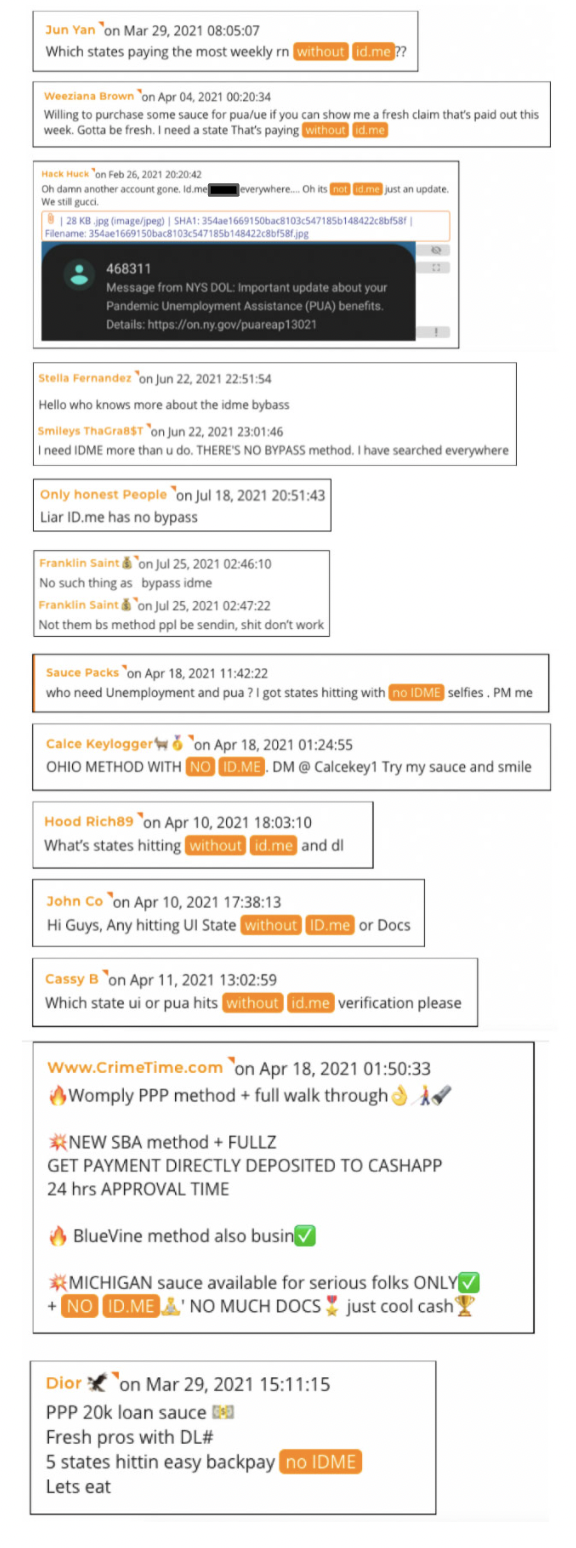

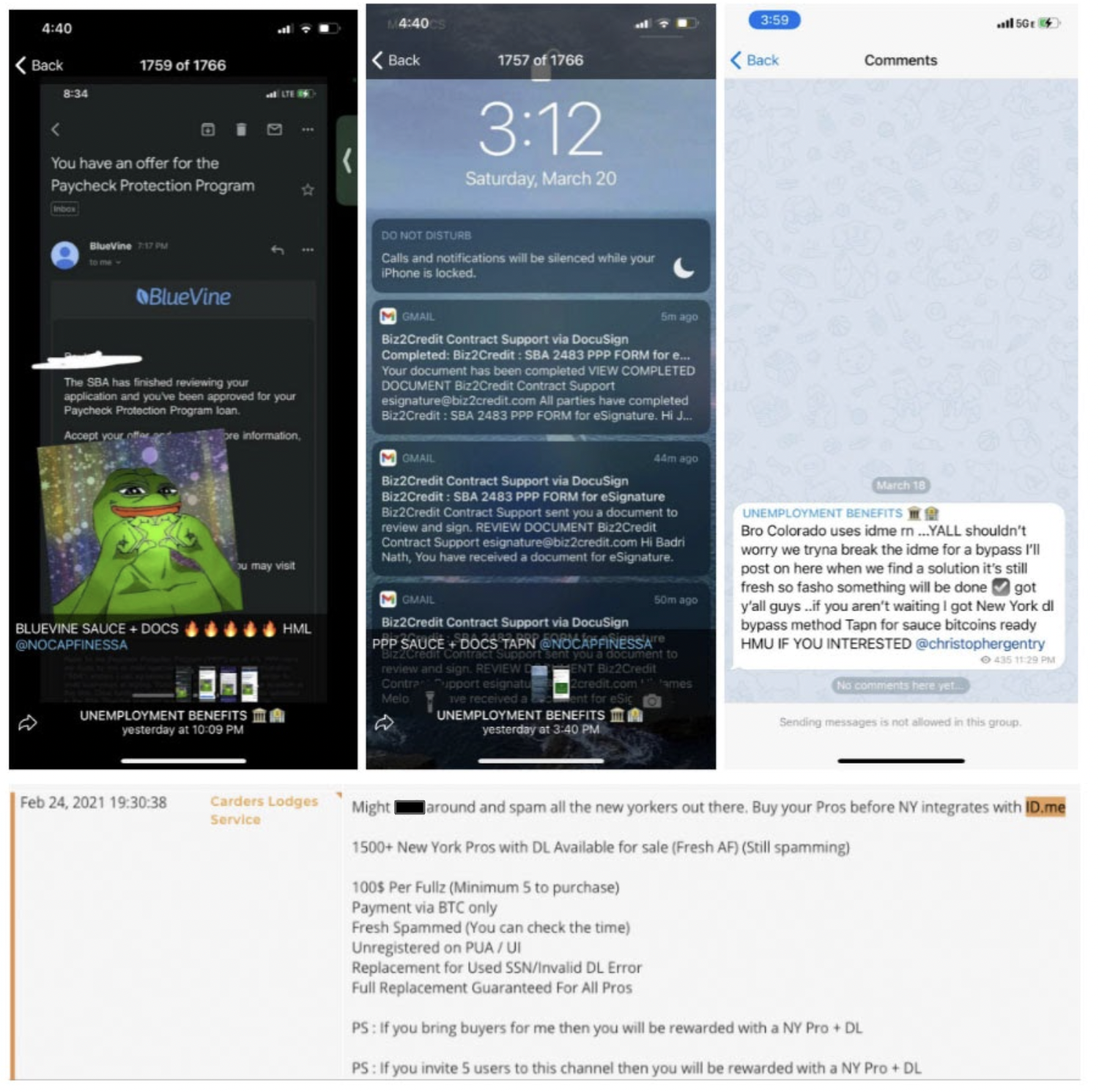

What the criminals are saying

ID.me set up a dark web Threat Intelligence Cell to monitor criminal communications as they open-sourced attacks. As a result, we were able to actively watch crime rings as they adapted to new security controls and began to attack states and programs with weaker verification. Criminals often wrote our best testimonials. At the same time, we could see them actively organizing to target the weakest states and avoiding ID.me by name. As a result, we are confident that fraud rates are higher in states that moved more slowly and with weaker controls.

This dark web chatter is independently verifiable. Criminals use forums to organize; however, those same forums make them vulnerable to observation. Cezary Podkul, a reporter at ProPublica, wrote extensively about these forums in a deeply researched article.23

Conclusion

Prior to the pandemic, unemployment benefits had built in protections to control for identity theft and eligibility fraud. A state workforce agency would simply contact an employer to confirm a UI claim was valid. If the employer didn’t recognize the employee on the claim, or disputed the claim, they would engage with the workforce agency. Employers were incentivized to respond if something was amiss as they risked paying a higher UI tax for higher turnover rates.

This feedback loop effectively contained fraud as experts cited above note. Fraudulent claims totaled less than 1% prior to the pandemic. Improper payments were mainly more mundane errors like overpayments if an individual found work but continued to receive payment.

During the pandemic, the employer to workforce agency feedback loop was removed. This effectively took the brakes off the system. With a trillion dollars of unemployment entering the economy, relaxed controls, and fewer feedback loops, conditions were ideal for a criminal “Super Bowl.”

It will likely take years to fully audit the fraud that happened during the pandemic. It is quite possible they will never be able to fully audit the fraud due to its vast scale. In the interim, all available data points from the states, experts, and our data supports $400 billion dollars lost.

Footnotes

- Pandemicoversight.gov, “Funding Overview.” Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.pandemicoversight.gov/data-interactive-tools/funding-overview

- https://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2021/19-21-004-03-315.pdf

- “FAQ’s – General Unemployment Insurance,” Virginia Employment Commission, accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.vec.virginia.gov/faqs/general-unemployment-insurance-questions#:~:text=Currently%20the%20maximum%20weekly%20benefit,earned%20in%20the%20base%20period.

- https://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2021/19-21-004-03-315.pdf

- “Gov. Whitmer solidifies anti-fraud measures to protect unemployed workers.” Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity. 29 Dec. 2021, https://www.michigan.gov/leo/0,5863,7-336-94422_97241_98585_99416_98657-574687–,00.html

- Christie, Bob and Nielson, Steve. “Scammers got $5.8 billion in fraudulent jobless payments from Arizona DES.” FOX 10 Phoenix, 30 Sept. 2021, https://www.fox10phoenix.com/news/5-8-billion-in-fraudulent-jobless-payments-were-sent-out-by-de

- Beam, Adam. “California’s unemployment fraud reaches at least $20 billion.” Los Angeles Times, 25, Oct. 2021, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-10-25/californias-unemployment-fraud-20-billion

- Kucera, Kris. Letter to John Albin. 16 Dec. 2020. https://auditors.nebraska.gov/APA_Reports/2020/SA23-12162020-July_1_2019_through_June_30_2020_CAFR_Early_Management_Letter.pdf

- Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. Protecting Consumers from Financial Fraud and Scams in the Pandemic Recovery Economy, Congressional testimony. Greszler, Rachel, 3 Aug. 2021, https://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Greszler%20Testimony%208-3-21.pdf

- Podkul, Cezary. “How Unemployment Insurance Fraud Exploded During the Pandemic.” ProPublica, 26 July 2021, https://www.propublica.org/article/how-unemployment-insurance-fraud-exploded-during-the-pandemic

- McGivern, Kylie. “FBI: Unemployment fraud is ‘a crisis situation.” ABC Action News, 1 July 2021, https://www.abcactionnews.com/news/local-news/i-team-investigates/fbi-unemployment-fraud-is-a-crisis-situation

- 12. Iafolla, Robert. “Pandemic fraud may shift, bring more business costs.” Bloomberg Law. 18 August 2021. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/pandemic-unemployment-fraud-may-shift-bring-more-business-costs

- Hassold, Crane. “Scattered Canary Cybercrime Ring Exploits the COVID-19 Pandemic with Fraudulent Unemployment and CARES Act Claims.” Agari, 19 May 2020, https://www.agari.com/email-security-blog/covid-19-unemployment-fraud-cares-act/

- “DOL-OIG Oversight of the Unemployment Insurance Program,” United States Department of Labor, accessed 17 Jan. 2022, https://www.oig.dol.gov/doloiguioversightwork.htm

- “Unemployment Insurance Protections in Response to COVID-19: State Developments,” National Employment Law Project, 27 March 2020, https://www.nelp.org/publication/unemployment-insurance-protections-response-covid-19-state-developments/

- “Labor Secretary Issues Directive to Employment Development Department to Suspend Unemployment Insurance Certifications,” California Labor and Workforce Development Agency, 23 April 2020, https://www.labor.ca.gov/2020/04/23/labor-secretary-issues-directive-to-employment-development-department-to-suspend-unemployment-insurance-certifications/

- Daily, Ryan. “DeSantis Waives Unemployment Re-certification Rule, In Effort To Speed Clearing Of Massive Backlog,” WUST Public Media, 16 April 2020, https://wusfnews.wusf.usf.edu/2020-04-16/desantis-waives-unemployment-re-certification-rule-in-effort-to-speed-clearing-of-massive-backlog

- “Executive Order 2020-76: Temporary expansions in unemployment eligibility and cost-sharing – RESCINDED,” Michigan.gov, accessed 17 Jan. 2022. https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90705-528456–,00.html

- “COVID-19: States Struggled to Implement CARES Act Unemployment Insurance Programs.” U.S. Department of Labor, 28 May 2021. https://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2021/19-21-004-03-315.pdf

- “COVID-19: States Struggled to Implement CARES Act Unemployment Insurance Programs.” U.S. Department of Labor, 28 May 2021. https://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2021/19-21-004-03-315.pdf

- Hammel, Paul. “Auditor alleges lax oversight over covid relief payments by Nebraska Labor Department.” Omaha World Herald, 16 Dec. 2020, https://omaha.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/auditor-alleges-lax-oversight-over-covid-relief-payments-by-nebraska-labor-department/article_96f8d7d2-3fdf-11eb-a7bd-b75d084ead76.html

- “DES Expands ID.me Identity Verification for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Claimants.” Arizona Department of Economic Security, 19 Nov. 2020, https://des.az.gov/sites/default/files/media/newsrelease-11-19-2020-DES-Expands-ID-me-Identity-Verification.pdf?time=1622851639590

- Podkul, Cezary. “How Unemployment Insurance Fraud Exploded During the Pandemic.” ProPublica, 26 July 2021, https://www.propublica.org/article/how-unemployment-insurance-fraud-exploded-during-the-pandemic